Director’s note:

Thinking behind the film’s visual structure

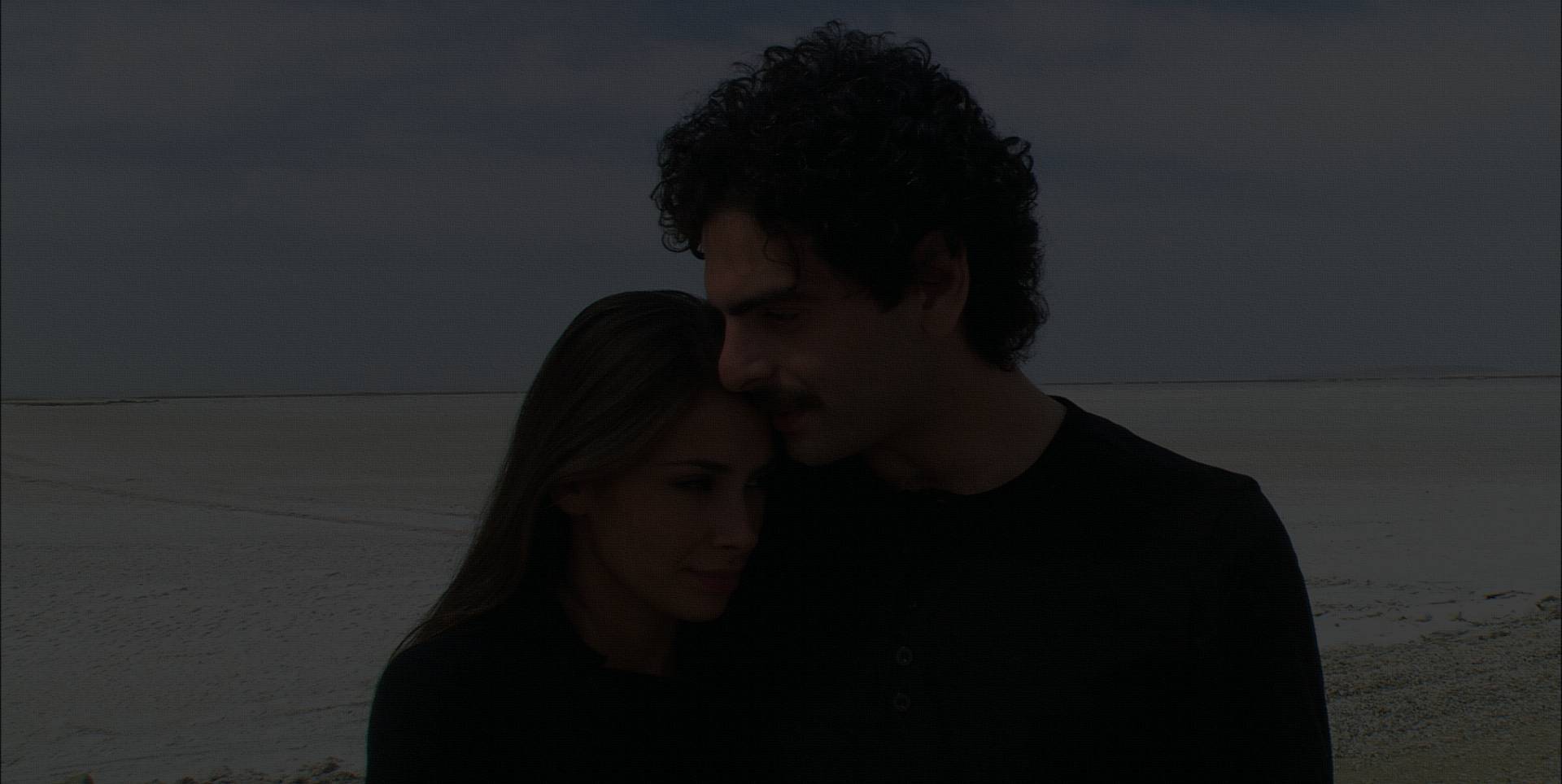

‘Dot’ tells the story of a man who regrets an offence he committed in the past and now wants to be exonerated. The film explores his struggle between the conflicting values of past and present. It is the story of a character growing, a character changing for the better.

In this respect, it could be said that the story possesses a sense of logic and belief that matches certain of the values and formal considerations fundamental to calligraphy. One of these is the concept of ihcam that I will explain a little later.

A film comprising a single fluid shot

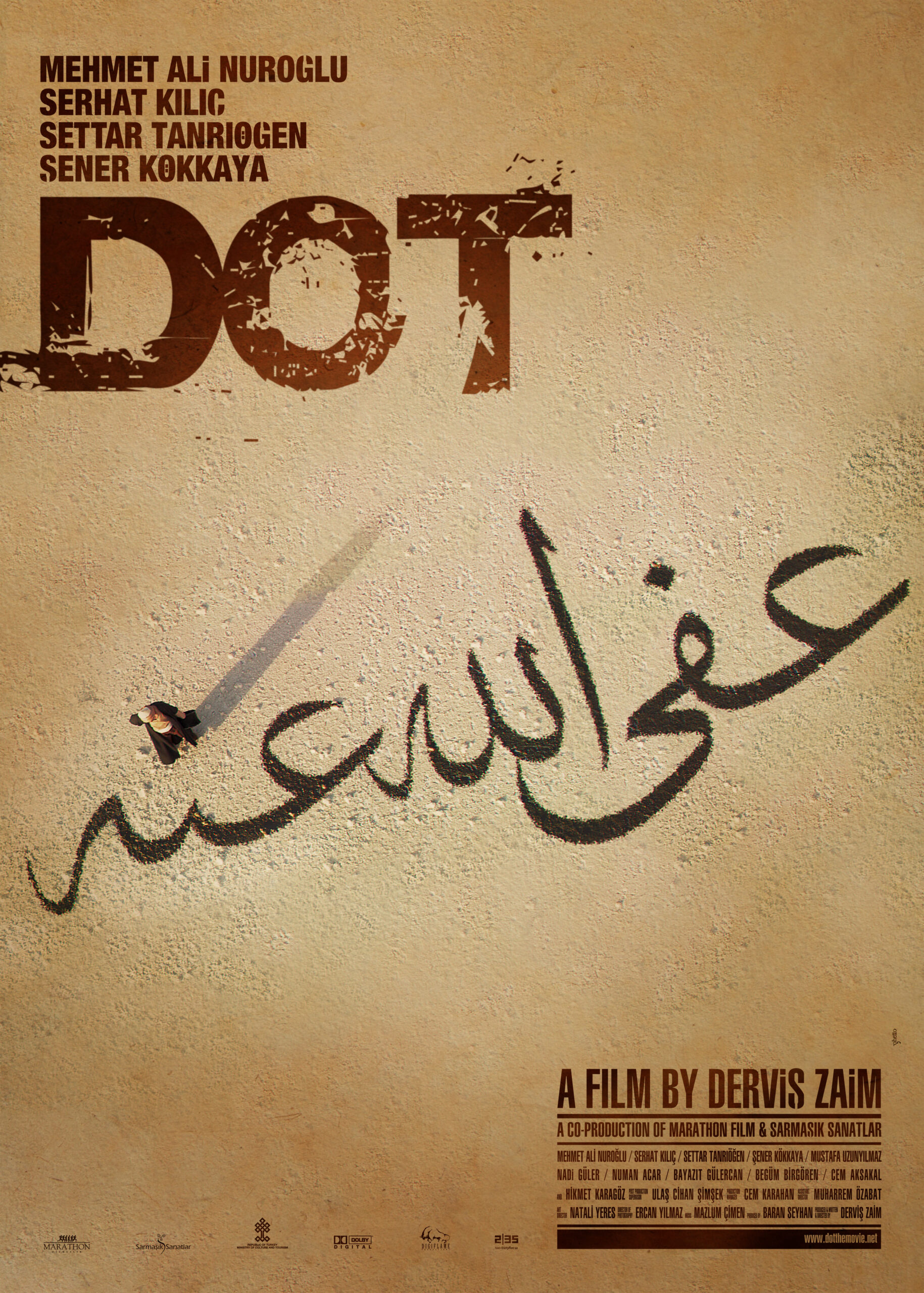

The film will be based on certain of the formal qualities associated with Ottoman calligraphy and endeavour to build a cinematic narrative that reflects this atmosphere.

One of the concepts I have borrowed from traditional Ottoman calligraphy to achieve this is that of ihcam. In calligraphy, the term ihcam refers to forming a character in a single stroke. When calligraphers employ ihcam, they produce a motif or composition in one continuous stroke.

In the same way that a calligrapher might choose to produce a motif in one stroke, I plan to present the film as an uninterrupted narrative, to set it up as a single fluid shot to give the sense of continuity.

Events within the film, whether past or present, is narrated as though happening in real time. There are no interruptions, no cuts, meaning the story is told ‘in one go’ to evoke the intended sense of continuity. Even in the case of flashbacks, I carry on using this same technique. While, for instance, the film’s central character Ahmet operates in the present tense, he occasionally recalls the past, at which point the narrative backtracks to reveal those past events shaping his present experience. But in portraying the past and present, the film deliberately eschews formal cuts or other transition techniques used to differentiate the two tenses. I attempt instead to present events in the single stroke that characterises ihcam so that events elide into an unbroken continuum. In this sense, time and place are constructed as an interconnected whole.

Location, light and colour

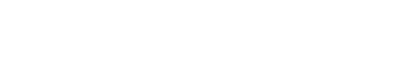

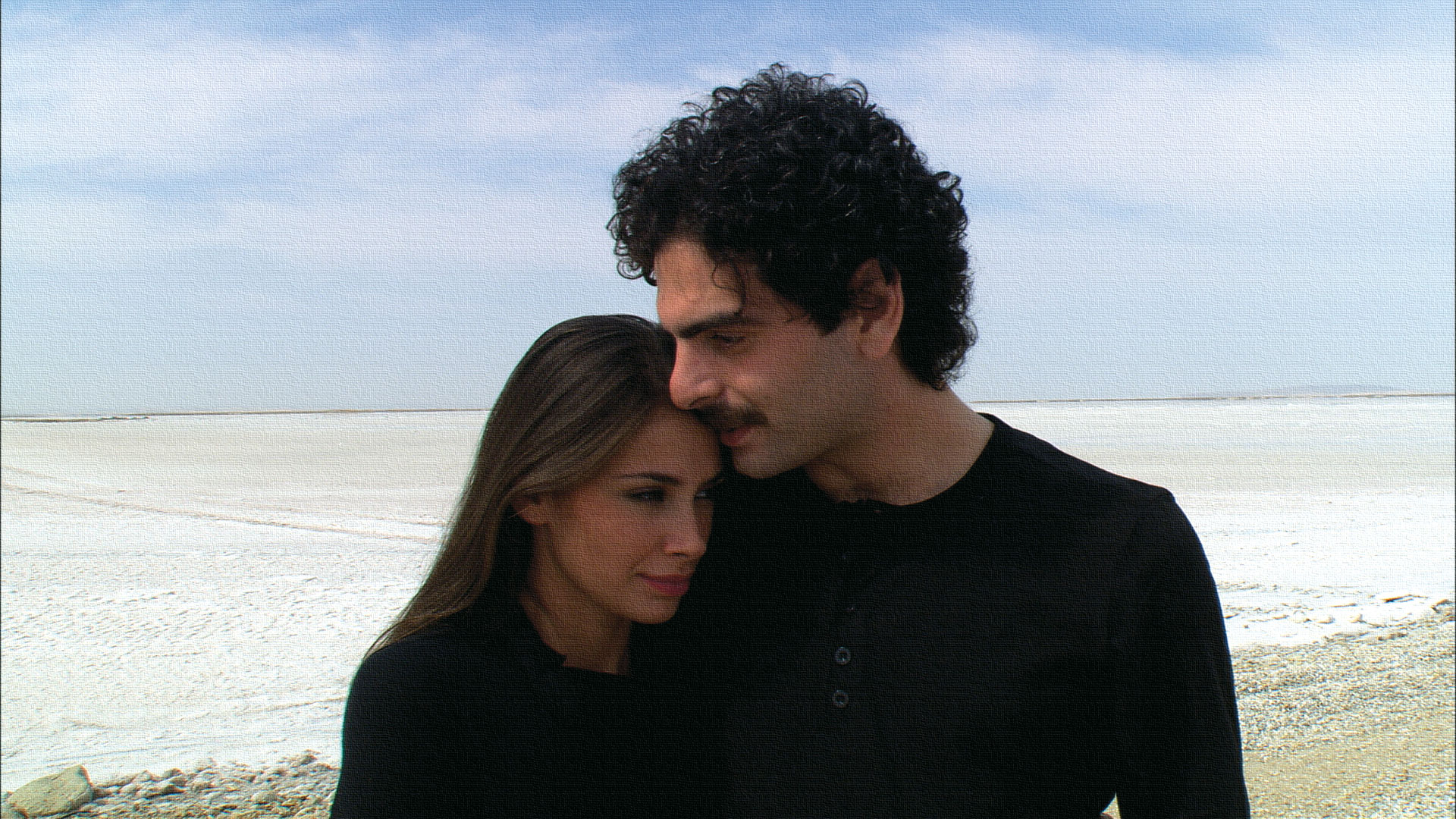

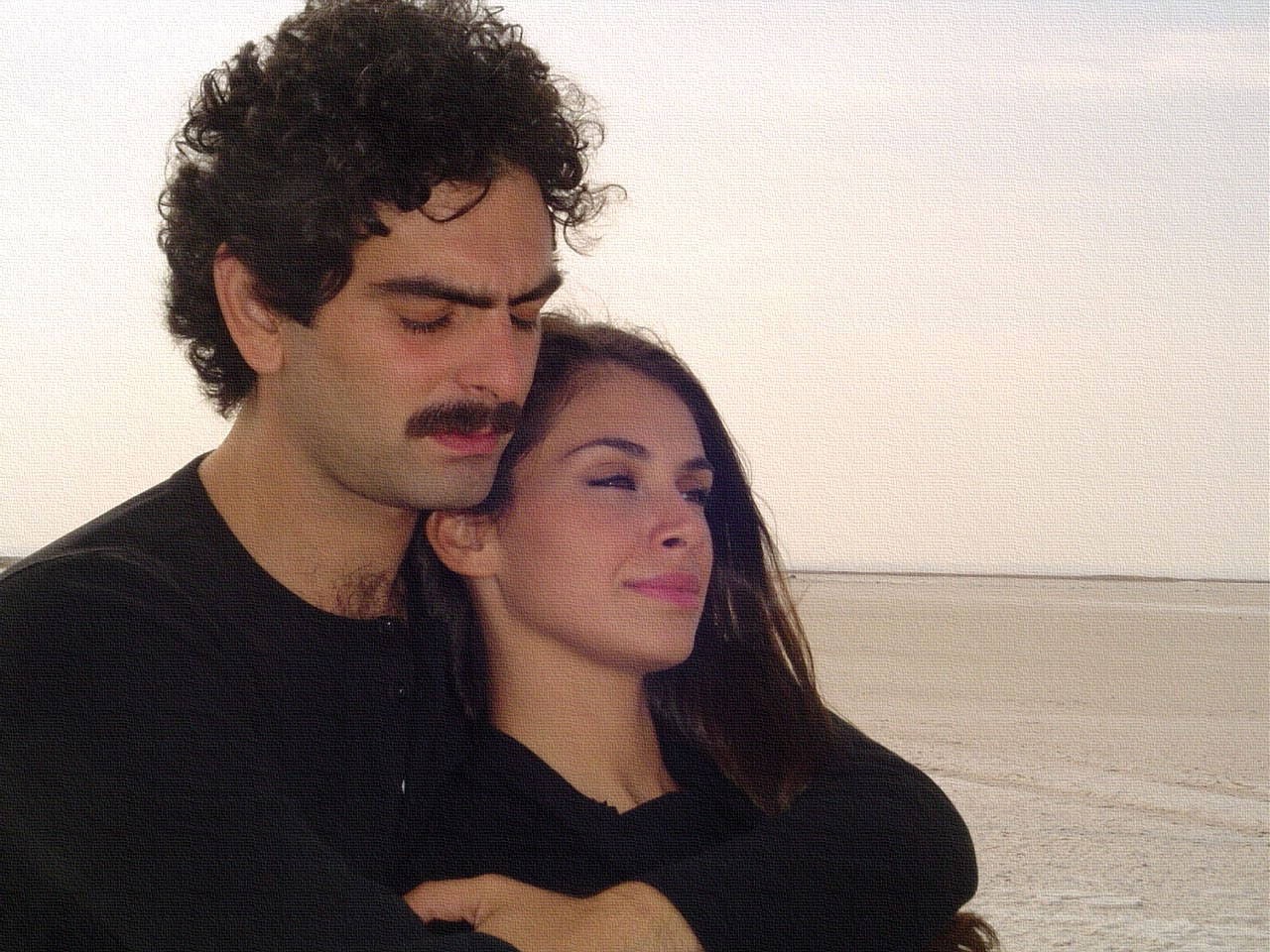

There are a few additional points that should be mentioned in terms of colour, light and art direction. As far as shooting locations are concerned, I used the Konya Salt Lake, the second largest salt lake in the world, and to shoot exclusively exteriors. In setting the action of the film in the vast, empty landscapes of the salt lake against a backdrop of endless white, I hope to evoke the white paper and the black ink typically used in calligraphic work. The association with calligraphy is further endorsed by favouring black or dark grey tones in the choice of costumes, props and vehicles. In this respect, the film’s overall palette comes close to the black and white colour scheme characteristic of calligraphy.

Utilising authentic sources and possible risks

I aim to produce a cinematic narrative that gravitates towards authentic sources. My motive in doing so is to take advantage of local history and traditional art forms in an attempt to enhance the content and narrative language of the film.

The film tackles authentic sources in a bid to capture a different cinematic approach, while at the same time reflecting the intellectual and formal considerations that have developed in contemporary cinema.

Characteristics of Ottoman calligraphy

Mention of calligraphy tends to evoke artistic handwriting in Arabic script. Generally speaking, the plastic arts had more of a decorative quality in Islamic culture and rarely extended beyond the artisanal context. As in Islamic society, the painting and sculpture traditions of the west had little place in the Ottoman state. Yet the fact that western art failed to flourish also meant that calligraphy became the most prominent craft in Islamic culture and the one that underwent the most striking process of aestheticisation. This is perhaps more understandable given the importance that calligraphy gained on account of the Koran. Unlike the art work that traditionally decorates churches, mosques are ornamented with calligraphic motifs written in Arabic script. In every mosque in Turkey, for example, the dome is surrounded by eight panels bearing the names Allah, Muhammed, Ebubekir, Ömer, Osman, Ali, Hasan and Hüseyin respectively. In other words, calligraphy has become the only legitimate symbol of divinity and sanctity in Islam.

There is value at this point in mentioning briefly the difference between calligraphy and oriental scripts. Chinese and Japanese characters have deviated little from the pictographic origins that characterise most alphabets and as such have much in common with calligraphy. Ultimately, the Arabic alphabet originated from Egyptian hieroglyphics, another example of pictography, and grew from the branch of alphabets associated with Semitic communities in Phoenicia. It would therefore be fair to say that after a time, the Arabic alphabet began to deviate fairly radically from pictorial writing. But when calligraphy started to take off, the Arabic alphabet underwent an abstract form of aestheticisation that had nothing to do with pictorial illustrations.

A number of master calligraphers flourished in Persia. But once the Ottoman state evolved into an empire and effectively became the face of Islamic culture, it was Ottoman calligraphers who enriched and enhanced the art form to a degree never before seen in Arabic and Persian centres. Even today, Turkey and specifically Istanbul are regarded as one of the leading centres, if not the leading centre of calligraphy.

Relationship between the film and calligraphy

The film takes its subject from calligraphy; it is also shaped by the art form in terms of both form and content. The majority of Islamic poets interpreted everything in life as a book or a verse and endeavoured to see calligraphy in everything animate and inanimate that existed in life. The value system shaping Ahmet, the lead character’s central dilemma thus derives from the moral values typically associated with a calligrapher. Ahmet is, after all, a calligrapher, but one who has committed murder. He is psychologically tormented as a result, and his reading of many of the objects around him is coloured by this perspective. One of the questions posed through the character of Ahmet is this: at what point in life can we be said to have fulfilled our moral responsibilities? Do we actually fulfil our obligations if we take action in the right direction but fail to obtain the intended outcome? Is it right to blame people for things that go awry when they have done all they can to make them right? In short, the film focuses on one of the fundamental questions of moral philosophy. The crux of the film could be described as an examination of the link between actions, the people behind those actions and their consequences. I personally think that focusing on just one of these areas could produce misleading consequences. If morality was concerned with consequences alone, a bizarre situation could result whereby even the most well-meaning person could sometimes do wrong. But on the other hand, it would be just as bizarre if morality had nothing to do with consequences. How could the consequences of our actions have no importance?

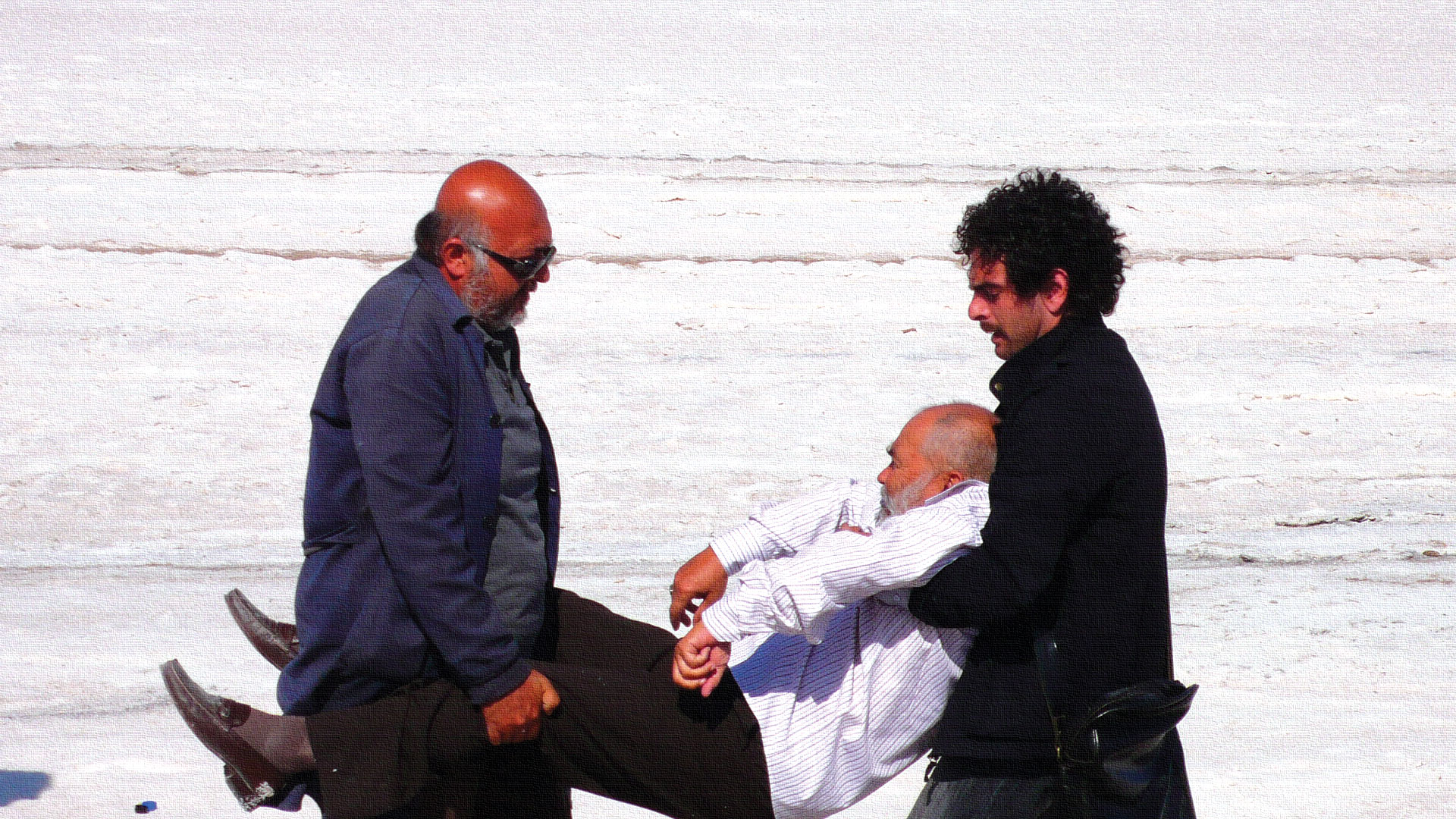

Ahmet, the central character

At the beginning of the film, Ahmet is portrayed as someone who strays from the spiritual or moral characteristics that a calligrapher should possess. Ahmet is someone who has been to jail in the past for reproducing handwritten Korans of high artistic value and trying to sell them at a vast profit on the art market. On top of that, having left jail, he is dragged into a similar deal to smuggle a handwritten Koran, ostensibly as a favour to a friend. In fact, the smuggling deal in which he gets involved propels him towards committing murder. Having performed the act, he begins to be tormented by his conscience, albeit in only a minor way.

Ahmet is aware that his past misdemeanours are not sanctioned by the art of calligraphy. He seeks exoneration. But because he is dragged along by events, the thing he must do to be forgiven turns out to be connected once more to calligraphy. Within the framework of calligraphy Ahmet finds himself having to decide between committing a crime, being punished and finding forgiveness.

The project is the story of the personal choices of a man who regrets his past and now seeks exoneration. The perspective of the film is such that ‘humanity’ is regarded not only as a subject that is dragged along in the tide of external events at a specific moment in history or culture. Human beings are also seen as subjects with responsibility who try to stand on their own two feet, are able to make independent decisions concerning their own fate. In this sense, the project reflects an approach that follows the way orientalists view the east and specifically Islamic societies in particular; an approach that deviates from the negative presentation of human individualism in particular.

The project’s place in the modern world

Modern societies advocate self-defeat as a value, thus encouraging the whole system of consumer society and whipping up human ambition and desire. As a result, self-defeat has become the fundamental capital of today’s culture.

Every society favours certain qualities of human nature over others and picks out these qualities to create its own version of the ideal human being. The model human being today is a far cry from that of traditional communities, being characterised by selfishness, ambition, individualism and pride at ephemeral things.

Mevlana, the 13th century Anatolian mystic, saw every human attribute as a thing temporarily on loan. Consistent with this, he counselled people to transcend their own personal qualities, negative and positive alike, and to leave the qualities behind; the ultimate objective was, of course, to know oneself. In mirroring this awareness, I hope that the project will make at least a modest contribution to people of the modern age.