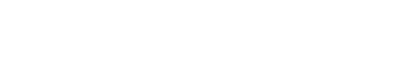

Synopsis:

Eflatun, a miniaturist who lives in 17th century Istanbul, the capital city of the Ottoman Empire, uses western style to paint a portrait of his son who has just died. But doing this gives him conflicting emotions, for painting “like a Venician or Frank” distances him from the style of painting taught to him by his own masters. While troubled with these kinds of thoughts, he is taken to the residence of an Ottoman vezir.

There he learns that a pretender to the throne, a prince named Danyal who has been leading a revolt against the Ottomans, has been captured in a distant Anatolian province and is to be executed. To ensure the identity of the rebel to be killed, the palace orders Eflatun to paint a portrait of the rebel in the western style. After receiving his orders, Eflatun sets out on a difficult journey into Anatolia accompanied by a select group of palace guards.

His apprentice Gazal is to be held in custody at the residence until Eflatun accomplishes his mission and returns. The group takes pity on a slave girl (Leyla) they meet on the way and bring her with them. They finally reach the caravansary where a surprise waits for them.

One Page Synopsis:

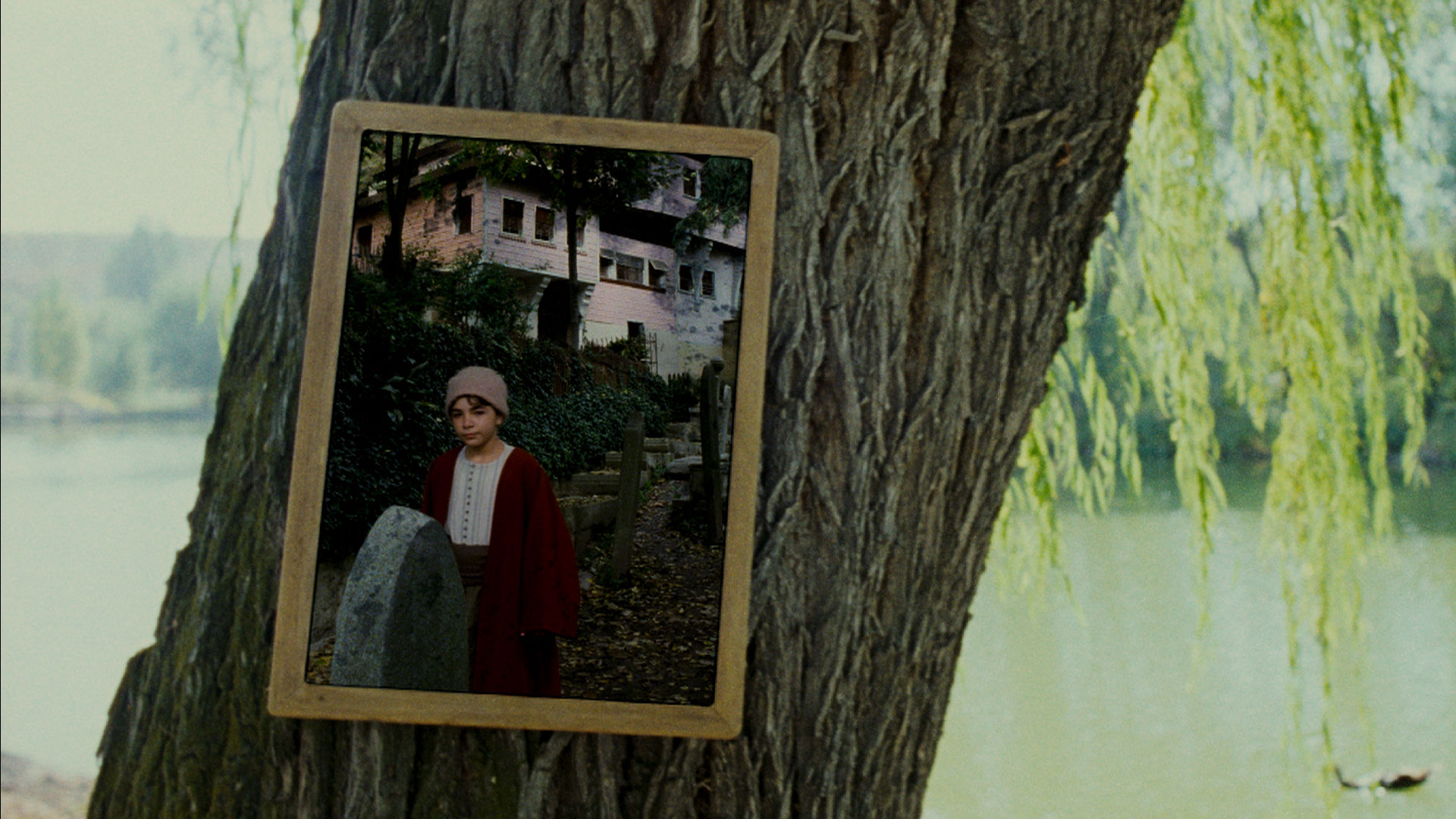

Miniature artist, Eflatun, a 17th century painter living in the Ottoman capital of Istanbul, uses western painting style to paint a likeness of his dead son. He is torn since he is using a style that opposes the method taught to him by his masters. Gripped by these feelings, he is taken to the palace. There he learns that Danyal, a royal prince who is a pretender to the throne, has been captured in a distant province and is to be executed. Because his severed head may decay on the journey to the city before it can be displayed, Eflatun is ordered to do a western style portrait of the rebel. Eflatun, along with a selected group of men from the palace, sets off on the difficult journey into Anatolia. His apprentice Gazal is to be held in ransom in the palace. The group pities a slave girl (Leyla) they meet and takes her along with them to the fortress where Danyal is being held. Eflatun draws the portrait of the rebel royal prince, but learns that the captive is actually Yakub, Danyal’s son. Yakub, taking advantage of Eflatun’s charity, tries to escape but is caught and killed. Osman (the leader of the group) decides to have Eflatun killed but his group is captured by Danyal’s rebels. Danyal has Osman killed in retribution for his son’s death. Danyal orders Eflatun to use western painting techniques to add elements to a western painting. The painting resembles the “Las Meninas” painting done by the Spanish artist Velazquez. Danyal orders Eflatun to paint in the Mehdi, the Moslem messiah, in a mirror in the painting for he believes that an image of the Mehdi will justify his cause. Eflatun perceives that the western painting may contain some miniature rationality. Eflatun tries to add a depiction of the Mehdi into the mirror by leaving the face a white blank, but cannot do it as it goes against his life and his masters. Leyla takes one of Eflatun’s miniatures that depict the Mehdi. She cuts out the depiction and pastes it onto the mirror in the painting. The rebels take the painting and leave. Freed, Eflatun returns to Istanbul with Leyla, where they marry. Eflatun is questioned when he goes to the palace to ransom Gazal. He learns that the Ottomans have defeated Danyal’s rebel army and that Danyal has been executed. He and Leyla go to his house where they find Gazal. Gazal tells him that Eflatun and the others were secretly followed throughout their journey by the palace and that is how Danyal was captured. Guilty for having painted in the western style, Gazal explains that he himself did a portrait of the pretender before the execution. Eflatun consoles Gazal and says that there would always be attempts to change time and space and that both Eastern and Western art did this, but in different manners.

Director’s Note:

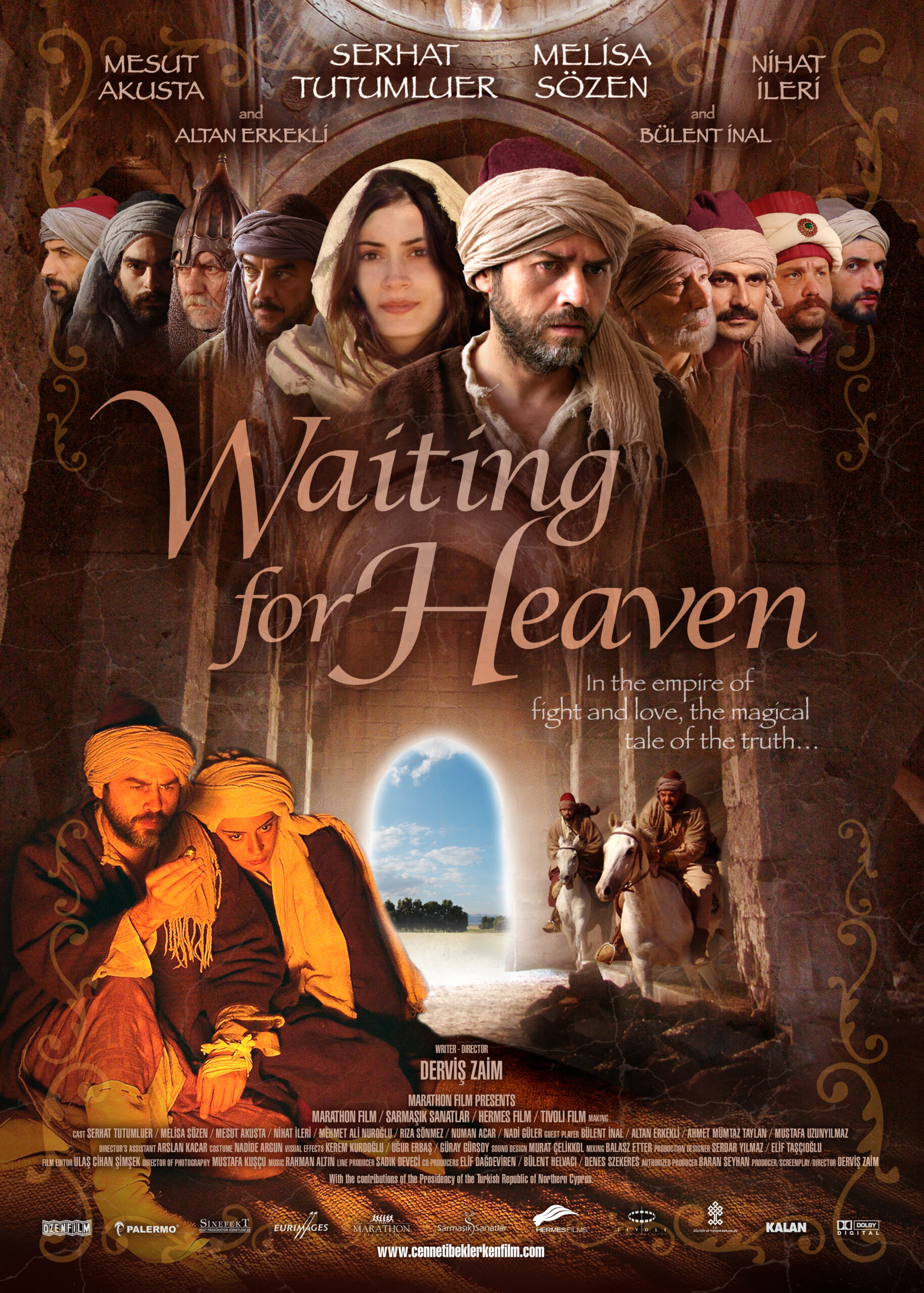

Given the atmosphere within the hegemonic and dominant mainstream commercial cinema in which the use of alternative types of expression tends to be restricted, as I was writing the screenplay for Cenneti Beklerken (Waiting For Heaven) I kept asking myself if it is possible to create a cinema that developes out of a different history and culture.

I wondered what kind of results I could get by using classical Ottoman miniature aesthetic as a tool for cinematic expression. During the preliminary work on the project I realized that while it is possible to use a traditional art form like miniature art (considered to be a form of dead art) to create a new aesthetic, the end result would be a highly experimental product. I also realized that there is a danger of impoverishing the film’s language if I used an expression that would narrow the aesthetic interest. To circumvent this danger, as I made use of Ottoman miniature art form I also tried not to weaken my use of other forms of expressions possible in contemporary cinema, and did this not just for the sake of referring to a classical art form.

In short, in this film I have tried to combine the use of both the manners inherent in European (Western) forms of painting and that inherent in Eastern miniature art forms. I also used the film’s content to further support this utilization of a new aesthetic. In this sense there is an overlap in my endeavor and the film’s subject.

Sources of Inspiration:

Sources of inspiration…