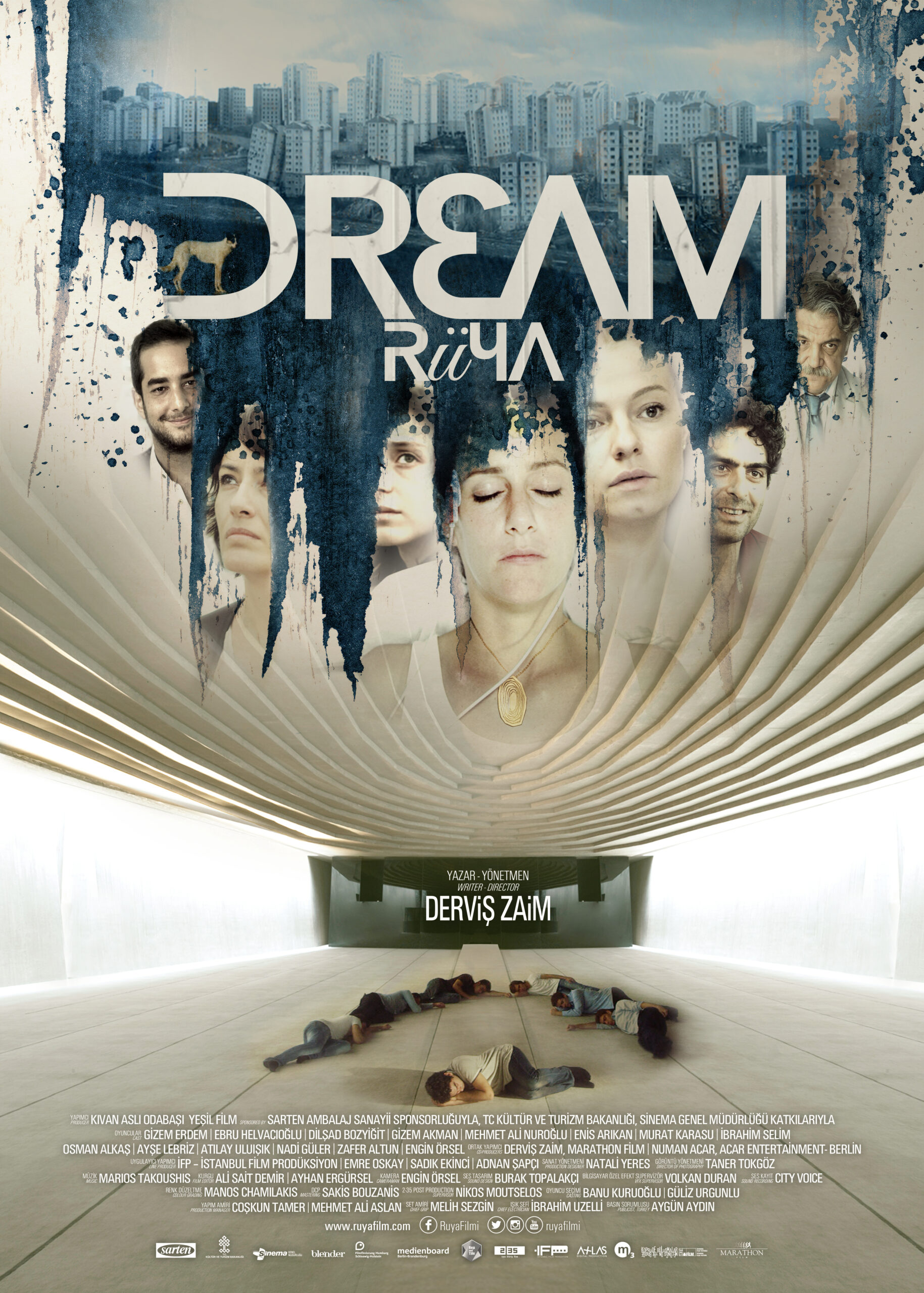

Synopsis:

Sine, a bright architect who is troubled by the shape of present-day architecture, designs an innovative, cave-like mosque inspired by the Seven Sleepers myth. The construction phase is beset with problems. Traumatized, Sine develops insomnia. She finally sleeps at a sleeping disorder clinic and sees herself in the myth of the Seven Sleepers. Waking from the dream, Sine has changed physically and psychologically. Each time she goes to the clinic, she changes and each time her new selves act differently.

Drama - Thriller

DREAM

Longer Synopsis:

Sine is a bright young architect who works for her uncle, Rüstem’s studio. Her real ambition is to be an installation-performance artist, but all the project proposals she has taken to galleries so far have been turned down. In her disappointment, Sine finds her life shading into one of the performances she longs to stage.

In reality, Sine has little choice but to carry on with architecture if she wants to make a living. She is increasingly drawn into the business of Rüstem’s office and even has to act as guarantor to a bank loan her uncle wants to take out. Stress and her growing sense of unease give Sine sleepless nights.

Faced with financial problems, Rüstem looks out for new business opportunities to save his studio. He is even prepared to engage in relationships that could be comprising from a legal point of view. The job of handling this less pleasant side of the business is delegated to Hakan, an enterprising young architect who also works at the practice. Hakan has a romantic interest in Sine.

As the muddy waters of the office swirl around her, Sine lands a job she thinks will make her happy. In years past her uncle’s studio built a residential complex for a small housing association in Istanbul’s suburbs. Yaren, a young guy who works for the association, tracks Sine down and asks her to design a small mosque for the complex. He says she should feel free to design something unconventional that showcases her architectural ability. Energized and inspired by this new proposal, Sine comes up with an original and inventive design for the mosque. When she shows Yaren the plans, he likes them a lot. In the contact they have during the evolution of the project we sense an unspoken attraction between them. Hakan begins to resent Sine and Hakan seeing each other and becomes jealous of their closeness. Sine makes it clear to Hakan that there is nothing between her and Yaren.

Construction begins on the innovative mosque for Yaren’s housing complex. But progress is later stalled by a large landslide, which destroys some of the homes owned by housing association members. The disaster persuades Yaren, his friends and colleagues to sue Rüstem’s practice as the responsible architect and contractor. But in the resulting trial the firm is acquitted. The landslide victims are understandably angry. And Sine is anxious to exonerate herself in their eyes.

But when she visits, they are a little rough with her. Rüstem finds out about the incident and files a complaint with the police for assault. Sine protests, but the prosecution goes ahead all the same. With the wheels of justice now in motion, Sine is powerless to stop a chain of events she doesn’t want to happen. Yaren, along with the housing association members, is arrested by the police.

Continuing insomnia leads Sine to spend the night at a sleep clinic. Here she has a dream that brings to mind the myth of the Seven Sleepers. Waking next morning, she has changed physically; she is a different person. Sine now has the freedom to do things she longed to do, but never could before undergoing this physical change. She tells her uncle, for example, that she wants to resign. On a return trip to the sleep clinic, she has a variation of the same dream. On waking, she is again physically different. She continues to accomplish things she was psychologically incapable of until now. Feeling bad for Yaren and his friends, who are still in custody, she goes to the police and withdraws the charges against them. The men are released. On each occasion, the changes that happen in Sine lead her to find different answers to life’s problems. Using different ways, she continues to battle with her destiny in order to be free, to attain happiness and spiritual catharsis. She is sometimes valiant, sometimes hesitant, sometimes timid, but she remains actively engaged in pursuing her dreams.

Director’s Note:

Sine is a young woman architect based in Istanbul. As the product of a heritage characterized by radical interruption and discontinuity, she aspires to a life that is informed by inherited values of history and tradition but combines continuity and change nonetheless. As an architect, she wonders whether styles of mosque that differ from the traditional structures handed down by history and culture are feasible.

She looks into the question of designing a new and different building that embodies the idea of continuity through change. In the meantime, she also has to survive on a practical level. The trouble is, she isn’t too successful at this. Is there a way to survive, but also to be more than an ineffectual witness to what is happening in the world? If so, what is it? Sine has no ready answers to this challenging question. On the one hand, she longs to drop everything and run. On the other, she risks both her personal safety and her architectural career to help the residents of a social housing estate that has collapsed in a landslide. In order to reach out to the victims she launches a massive and spectacular awareness campaign that can be seen by all of Istanbul. Sine represents hope in spite of everything.

She looks into the question of designing a new and different building that embodies the idea of continuity through change. In the meantime, she also has to survive on a practical level. The trouble is, she isn’t too successful at this. Is there a way to survive, but also to be more than an ineffectual witness to what is happening in the world? If so, what is it? Sine has no ready answers to this challenging question. On the one hand, she longs to drop everything and run. On the other, she risks both her personal safety and her architectural career to help the residents of a social housing estate that has collapsed in a landslide. In order to reach out to the victims she launches a massive and spectacular awareness campaign that can be seen by all of Istanbul. Sine represents hope in spite of everything.

A Fresh Narrative Inspired by Tradition

In Dream (Rüya), I aim to draw on the culture and history of Anatolia to create a fresh cinematic narrative style. To my mind, there are various structural features of Byzantine and Ottoman architecture which have the potential to enhance the language of cinema; and I set out to give these a central position in order to establish the narrative structure of the film.

The idea of continuity through change is central to the rhythm of Byzantine and Ottoman buildings, and it is an idea that I take as a basis film.

Repetition and Variation

Variation and repetition are two concepts I use at various levels of the film to illustrate the issue of continuity of tradition through change. Let me give an example. Analogous to the problematic of continuity through change, which is one of the core themes discussed, the central character is played by four different actresses in the course of the film. As different manifestations of the same character, these women sometimes react in different ways to similar situations according to the film’s dramatic structure. But they remain the same character. As these characters strive to preserve themselves despite so much change, the events they experience turn the film into a story of parallel universes. The film proceeds as a series of successive, but each time slightly different and therefore distinguishable shots, scenes and sequences.

Both the film’s story of parallel universes and the style used in telling these stories correspond with the style of rhythm found in Byzantine and Ottoman architecture, which is characterized by continuity through change.

Shifting the Audience’s Gaze

The film possibly covers new ground so far as the nature of the audience’s gaze is concerned. That is to say, with respect to its visual structure, the film tells the audience that it isn’t in a fixed, dominant and controlling position in terms of gaze. On the contrary, the film’s narrative structure and visual style shift the supposedly fixed, unchanging, controlling position of the audience’s gaze. For example, whenever the three women characters change, the view of Istanbul from the windows of the office where they work also changes. The office, however, is still the same office. By way of a crude comparison, in the way it handles the audience’s gaze, the film is intended to create an effect similar to that evoked by the skull in Holbein’s painting The Ambassadors.

A New Architectural and Filmmaking Process (Sancaklar Mosque)

A New Architectural and Filmmaking Process (Sancaklar Mosque)

The pursuit of alternative mosque architecture isn’t entirely foreign to the Islamic architectural tradition in Turkey, even if examples are few in number. A notable recent addition is the Sancaklar Mosque designed by the architect, Emre Arolat. Set in an outlying suburb of Istanbul, the mosque was named Best Religious Building at the 2013 World Architecture Festival in Singapore. As such, the Sancaklar Mosque provided crucial material for the project given its discussion of alternatives to, and variations on traditional architectural styles. It also meant that we incorporated the building of the mosque into the film. The shooting of the film was part of the building process. I should also add that the mosque’s physical resemblance to a cave was what inspired the link with the Legend of the Seven Sleepers.

The Legend of the Seven Sleepers

The story of the Seven Sleepers is a story from the Koran that tells of seven youths reawakening after a long slumber. As a variation on the resurrection motif, it has echoes in other faiths, among them Christianity and Judaism. The devout youths of the story face antagonism from the pagan community when they give voice to their beliefs. To escape punishment, they take refuge with their dog in a cave and fall asleep. By the time they wake again centuries later, the pagan era has ended and, with it, the repression of earlier years. Known as Kıtmir, the seven sleepers’ dog is widely believed to protect man from evil.

The Seven Sleepers and the Film

The film inclines towards interpreting the Legend of the Seven Sleepers as a utopian philosophy. When the sleepers realize they won’t be able to achieve their utopia, they go to sleep in order to protect it. By sleeping, they endeavour to protect their existing dreams until this utopia comes into being. The character of the woman architect at the centre of the film longs to sleep in order to protect her humanitarian, professional and artistic utopias. However, she is thwarted in this by insomnia. Spurred by an unconscious impulse, she designs a space where she can sleep safely and comfortably and so, in turn, protect her utopias. The space bears a strong resemblance to a cave. The mosque, which brings to mind the legend of the Seven Sleepers, is the real-life Sancaklar Mosque. The building of the mosque happened to coincide with part of the film’s photography.

Year:

2016

Writer & Director:

Derviş Zaim

Producer:

Yeşil Film

Sponsored by:

Sarten Ambalaj Sanayii

Supported by:

T.C. Kültür ve Turizm Bakanlığı, Sinema Genel Müdürlüğü katkılarıyla

Cast:

1 st Sine: Gizem Erdem, 2nd Sine: Ebru Helvacıoğlu, 3rd Sine: Dilşad Bozyiğit, 4th Sine: Gizem Akman, Yaren: Mehmet Ali Nuroğlu, Hakan: Enis Arıkan, Rüstem: Murat Karasu, Avukat İlbey: İbrahim Selim

Co-Producers:

Derviş Zaim, Marathon Film, Numan Acar, Acar Entertainment- Berlin

Line Producers:

İFP – İstanbul Film Prodüksiyon, Emre Oskay, Sadık Ekinci, Adnan Şapçı

Production Designer:

Natali Yeres

Director of Photography:

Taner Tokgöz

Music:

Marios Takoushis

Editor:

Ali Sait Demir, Ayhan Ergürsel

Cameraman:

Engin Örsel

Sound Design:

Burak Topalakçı

Casting:

Banu Kuruoğlu, Güliz Urgunlu

Visual Effects:

Volkan Duran

Production Manager:

Coşkun Tamer, Mehmet Ali Aslan

Chief Grip:

Melih Sezgin

Chief Electrician:

İbrahim Uzelli

Sancaklar Mosque Architect:

Emre Arolat, EAA – Emre Arolat Architects

Cast:

Hüseyin: Engin Örsel, Zafer: Zafer Altun, Haciz Memuru: Adnan Şapçı, Toplu Konut Sakini: Nadi Güler(Ahmet), Mehmet Şanlıer, Zülfikar Ateş, 3d Şirket Patronu: Murat Kılıç, Banka Görevlisi Kız: Siğnem Selçuk, TV Muhabiri: İsa Sağlam, TV Spikeri: Cenk Mutluyakalı, Parktaki Polis: Can Şıkyıldız, Aras Kösedağ, Polis Komiseri: Emre Oskay, Uyku Hastalıkları Hemşire: Merve Yayla, Uyku Hastalıkları Doktor: Mert Yusuf Özlük, Baskına Gelen Mali Polis: Doğan Dileroğlu

Guest Appearances:

Bürokrat: Osman Alkaş, Küratör: Ayşe Lebriz, Polis Memuru: Atılay Uluışık

Thanks:

Zeki Sarıbekir, Branimir Mladenov, Sevil Akı, Mixer, Art on İstanbul, Selim Bilgiç – 36 mm

Marathon Film – Yeşil Film 2016